name_of_the_data_object %>%

ggplot() +

geom_histogram(aes(name_of_the_column), bins = 3)7. Filtering data and testing means (one-sample t-test)

Written by Tom Beesley & John Towse

Lectures

Watch Part 1

Watch Part 2

Watch Part 3

Watch Part 4

Download the lecture slides here

Reading

Chapter 12 of Howell

Today we will look in a bit more detail at people’s estimates of the average UK salary. We will first plot this data using geom_histogram() and also geom_boxplot(). When we do this, we’ll see that there are some unusual values, and we’ll need to do a bit of data wrangling to remove them, using the filter() command. We’ll then turn to the conceptual ideas of the lecture - how can we tell if the mean of our sample is unusual, or whether we would actually expect this mean value under the null hypothesis? Finally, we’ll continue to develop our skills in data visualisation by exploring geom_density() plots.

Pre-lab work

There is an online tutorial. Please make every attempt to complete this before the lab!

Create a folder for Week 7

Download the csv file for Week 7 and upload it into this new folder in RStudio Server.

RStudio tasks

Creating a new R Markdown document

Like last week, create a Week 7 folder and a new R Markdown document

Delete everything, back to the first title (## R Markdown)

Change the title to Task 1 - plotting the salary data

Task 1 - Plotting and filtering

Below the title, insert a code chunk. Click on the menu “Code” -> “Insert Chunk”.

Add in the code

library(tidyverse)Next, add a

read_csv()command to get the data - you’ve done this every week, so this should be familiar. Remember when reading in the data, you need to assign it to a new data object.Let’s draw a histogram of the salary estimates:

Once you’ve got the code to run, you’ll realise that the setting

bins = 3is not a good setting to see the distribution of data. Play around with the number of bins for the histogram until you are happy that you can see the distribution of the scores more clearly, including some of the more extreme values.You will see that we’ve got some quite unusual values here. For example, some people think the average salary is less than £10,000 and some people think it’s more than £70,000! It’s unclear what to make of these values. For example, maybe the £5,000 estimates meant to put £50,000? Quite often when we get our “raw” data, it contains extreme values like this, and we need to consider removing them. Let’s run these two lines of code, using

arrange(), to see what exactly those high values are:

arrange(name_of_the_data_object, name_of_the_column) # order by lowest first

arrange(name_of_the_data_object, desc(name_of_the_column)) # order by highest first- We’ll need to remove these high values to get a better sense of the distribution. Let’s use a

filter()command to do this. We need to make a decision about what values to exclude. In later labs we’ll look at a more systematic process of removing outliers, but for now, let’s just remove any that are over £50,000. Edit thefilter()command to keep only those estimates that are below £50,000 (<). Remember that the filter command keeps the data that is TRUE according to the expression.

name_of_the_data_object %>%

filter(*missing*) # add your expression hereIf you completed that last step correctly you’ll see an output in the console (or in your .Rmd) showing a data object which has 128 rows and 5 columns. However, your data object has not actually changed in the environment. This will still be showing as 137 observations (rows). So while the filter command will take out those large estimations, we haven’t actually changed the data object at all. To do this we need to assign (<-) the result of our filter command to the object.

Think about what you need to do to assign the result of the filter to a data object. You assign the result to the same object name you’ve been using (that is, overwrite it), OR you can assign the result to a new data object (e.g., my_object_filtered). It’s up to you.

We also want to filter out the very low estimates. Let’s keep all those values greater than (>) £6,000 (again, this is arbitrary, but we are just doing this so we can learn how to use

filter()). You can copy and edit the code above to run another filter command.When you’ve done both filter commands, the (new) object should have 122 rows. We can now plot the data again as a histogram. To do this, copy the earlier code for the histogram and edit it as necessary (if you’re using a new object for the filtered data, you’ll need to edit the code to reflect that).

And as you know, we can also look at the distribution as a boxplot, a violin, or a density plot. Feel free to add in your own code for other visualisations you might like to try.

It’s worth pausing at this point and documenting each of these steps you’ve done. Between each of your code chunks, you’ll want to write a sentence or two, describing the analysis you’ve done and what it produces.

Task 2 - One-sample t-test

We now want to know if the salary estimates are different to the actual average salary in the UK. According to Statista this is £34,963. Our hypothesis might be that people are inaccurate - they overestimate or underestimate the average UK salary. Let’s test that.

- First, let’s calculate the mean and sd of the column:

mean() # hint: object$column

sd() - Now we can compute a t-statistic and check whether this mean is significantly different from the expected mean. We do this with

t.test():

t.test(x = name_of_the_data_object$name_of_the_column, mu = value_of_expected_mean_under_null_hyp) Copy the above code into your document and edit it to conduct a one-sample t-test. You need to provide the sample of data on which you want to conduct the test, and the expected mean under the null hypothesis. Remember our hypothesis stated above is that people are not accurate. Your calculation of the mean should tell you whether they numerically overestimated or underestimated. But would we expect such a result under the null hypothesis? Run the t-test and note the p value. How likely is it that we would see data like this under the null hypothesis? The p value ranges from 0 to 1. If it is very low - typically we say p < .05 - then we conclude our result is unlikely under the null hypothesis and it is therefore a significant result.

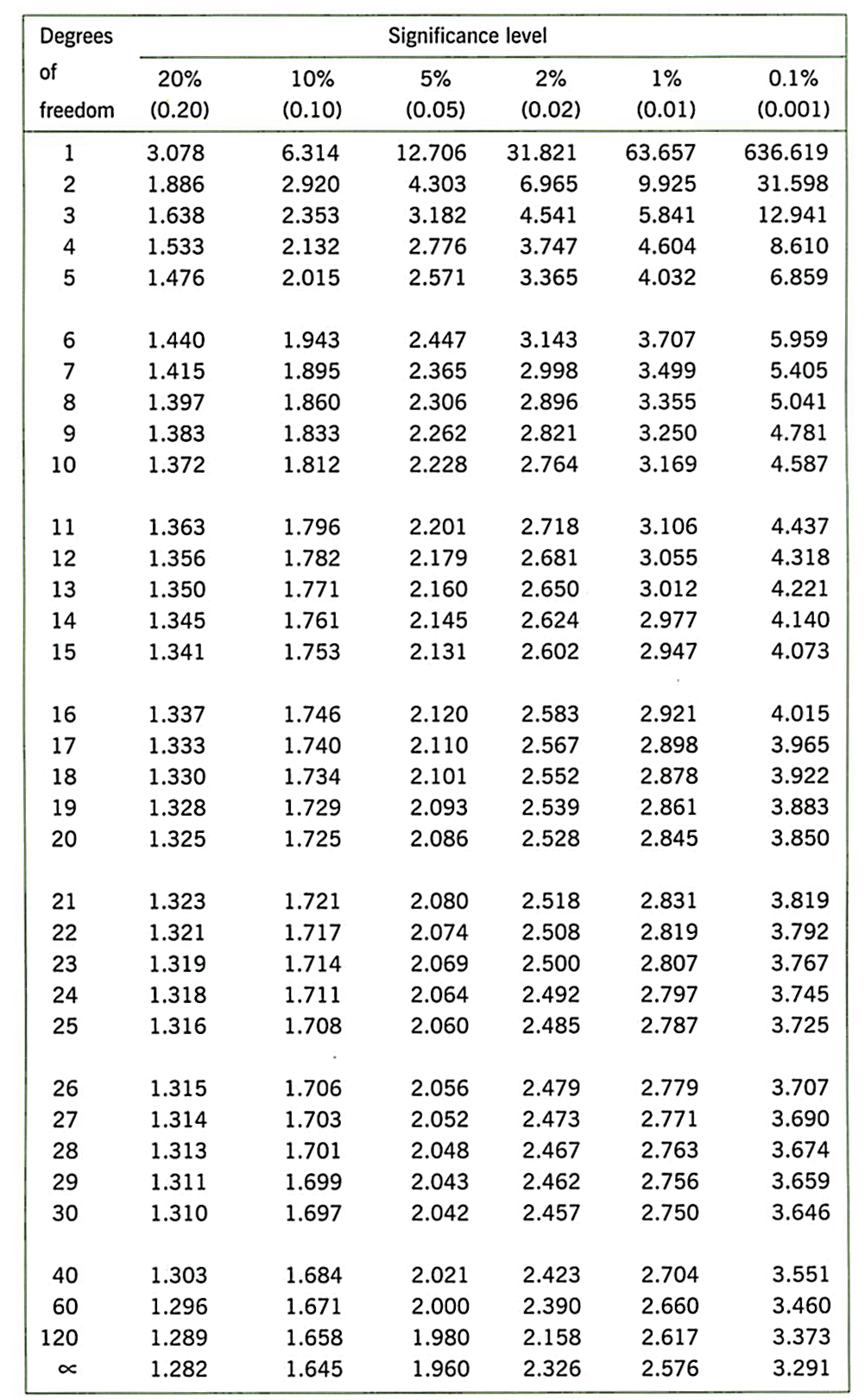

- What is the critical value of t in the t-distribution table, for this sample size? Degrees of freedom is N - 1.

Task 3 - Sample size, size of effect, and the one sample t-test

In the lecture this week, Tom used an application to show the process of sampling data. You can access this application at the link below. There are three “parameters” you can change in this:

The true mean of the effect: Think of this like the bias that was set up in your deck of cards last week. There is some true state out there in the world, and we are going to draw samples from a distribution of data that has a mean that equals this value. If you make this 100, then the true mean is equal to that under the null hypothesis (there is no effect).

The standard deviation of the data: This sets how variable the data are in this population. If the data are more variable, then our samples will produce estimations that are less accurate of the true mean value.

The sample size: How many observations are drawn in the sample. These are represented by the yellow circles in the plot.

Each time you draw a sample the data points are plotted in yellow and the mean of the sample is marked with the red line. The application also runs a one-sample t-test against the expected mean under the null hypothesis, of 100. The null hypothesis is also represented by the static distribution presented in grey, centred on 100.

Things to try:

Start with a sample size of 10, and a mean of the effect of 110 (SD = 15). How often do you get a significant result (p < .05) when you draw a new sample?

Now try changing the mean of the effect to 120. Does this increase or decrease the likelihood of getting significant results? What about changing to 130?

Now keep the mean effect constant (say 110), but increase the sample size. Try 5, then 10, 15, and so on. Does this increase or decrease the likelihood of getting significant results?

Set the mean of the effect to 100 and the sample size to 10. Keep drawing new samples, noting each time the p value. You will evenutally get a p value of < .05. What type of error is this?

Click here for the one-sample t-test application

Task 4 - Practising filtering

- Filtering is very useful for selecting certain sub-sets of our data. Here we have given you an example of how we select a sub-set of data based on two conditions from two different columns:

name_of_the_data_object %>%

filter(home_location_in_UK == "NW" & sibling_order == "oldest")We have given you a few different columns to look at and to use in practicing your filter commands:

sibling_order: what position in age was the respondent within their siblingshome_location: UK / Asia / Europe, etchome_location_in_UK: NW, NE, etc (NA is non-UK residents)attention_check: respondents were asked “click strongly agree to show you are paying attention” - some people failed this!!!

Gain some skills in filtering by trying to complete the following filters. Use the filtered data object that has 130 rows. We’ve put in () the number of rows you should see in the resulting object, after the filter.

Just those people who come from the North East (15 rows)

Those people who come from South East and are an only child within their siblings (7 rows)

Those people who failed the attention check (17 rows)

Those people passed the attention check, are from the UK, and are the oldest child (30 rows)

Those people who are NOT from the North West (hint: you’ll need to use

!=) (64 rows)Those people who are from the South East or (

|) the South West (33 rows)

Week 7 Quiz

You can access a set of quiz questions related to this week here.