download.file("https://github.com/lu-psy-r/statistics_for_psychologists/blob/main/PSYC122/data/week14/RTA_study1.csv?raw=true", destfile = "RTA_study1.csv")4. Week 14 - Chi-Square

Written by Margriet Groen (partly adapted from materials developed by the PsyTeachR team at the University of Glasgow)

This week we will focus on Chi-square as a measure of association between categorical variables.

Lectures

The lecture material for this week is presented in two parts:

- Theory - Associations between categorical variables (~23 min) Watch this part before you complete the reading and the pre-lab activities. The video has captions, in case you find that helpful. You can download the slides and a transcript from the links below the video.

- How to - How to do Chi-square in R (~19 min) Watch this part after you’ve completed the reading and before you attend the lab session. You can download the slides, a transcript and the example scritps from the links below the video.

Reading

The reading that accompanies the lectures this week is Chapter 19: Chi-square of the core text by Howell (2017). Please note that I might mention an alternative textbook in the lectures. The content is highly similar, but this year, we’ve decided to use Howell (2017) as the core text for PSYC121 and PSYC122. So no need to look at the book by Greene & D’Oliveira (2006).

Pre-lab activities

After having watched the lectures and read the textbook chapter you’ll be in a good position to try these activities. Completing them before you attend your lab session will help you to consolidate your learning and help move through the lab activities more smoothly.

Pre-lab activity 1: Calculating Chi-square by hand and interpreting the results

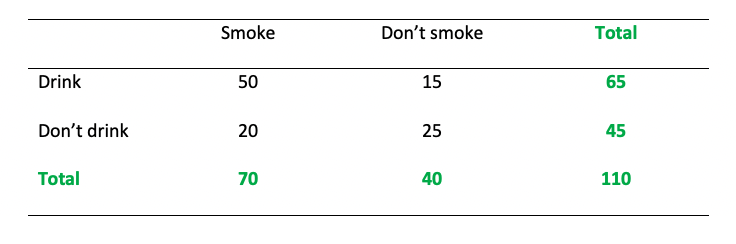

Is there a relationship between the number of people who smoke and the number of people who drink? Please note that the question is the number of people (frequency) and not how much people drink/smoke. Also not that these are fictitious data. You’ll need a table of critical values for Chi-square. This can be found in the ‘Week 14 – resources’ folder on Moodle.

Pre-lab activity questions:

- Complete the Pearson’s Chi-square test by hand using the data above and fill in the blanks:

\(\chi 2\) ( , N = ) = , p

- Can you reject the null hypothesis?

Pre-lab activity 2: Data visualisation - Creating a bar chart

We’ve mostly been using the ggplot2 package for visualising data. You can read a great overview of the ggplot2 package here. It also links to a ‘cheatsheet’ that you can download as a .pdf document. Lots of useful info on there!

With regard to visualising relations between categorical variables, the geom_bar() function is important. The following ‘recipe’ summarises what it does and how to use it.

TASK Have a look at the ‘recipe’ and read through it. Try to understand each step. Going through the example is particularly helpful.

Each ‘recipe’ has the same structure.

- First, it summarises what it is that you want to achieve when using that specific function. In the case of

select()it says “You want to extract specific columns from a data frame and return them as a new, smaller data frame.” - Then, it outlines a number of steps that you need to carry out when using this function. For

select()it outlines 2 steps: 1. Pass the dataframe to the function. 2. List the column(s) to return. - Finally, there is an example talks you through using the function with some data. For

select()it uses an example with data on the weather. - Additional information appears in extra boxes with a light-bulb icon. If you find those confusing, don’t worry about them at this stage.

geom_bar()- create a bar chart - recipe

Pre-lab activity 3: Getting ready for the lab class

Get your files ready

Download the 122_week14_forStudents.zip file and upload it into the new folder in RStudio Server you created.

If you get error messages when attempting to upload a file or a folder with files to the server, you can try the following steps:

- Close the R Studio server, close your browser and start afresh.

- Open the R Studio server in a different browser.

- Follow a work around where you use code to directly download the file to the server. The code to do that will be available at the start of the lab activity where you need that particular file. The code to download the file you need to complete the quiz is below.

Lab activities

In this lab, you’ll gain understanding of and practice with:

- conducting Pearson’s Chi-square in R

- interpreting Pearson’s Chi-square in R

- reporting the results in APA format

- when and why to apply Pearson’s Chi-square to answer questions in psychological science

Lab activity 1: Understanding the application of the Chi-square test

QUESTION 1

How does Pearson’s chi-square differ from Pearson’s correlation?

QUESTION 2

Chi-square test of independence would be appropriate when testing the following questions:

- What is the relationship between gender and soft drink preference? True or False?

- b.How do males and females compare in terms of wanting to be a psychologist when they leave school? True or False?

QUESTION 3

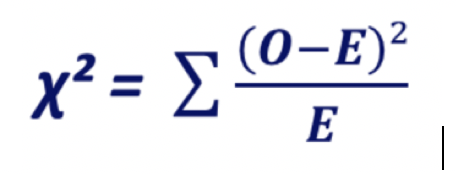

Write the chi-square formula below.

QUESTION 4

What were your answers to the pre-lab activity 1 questions? Please compare them with other students at your table.

+a. Complete the Pearson’s Chi-square test by hand using the data above and fill in the blanks:

\(\chi 2\) ( , N = ) = , p

+b. Can you reject the null hypothesis?

QUESTION 5

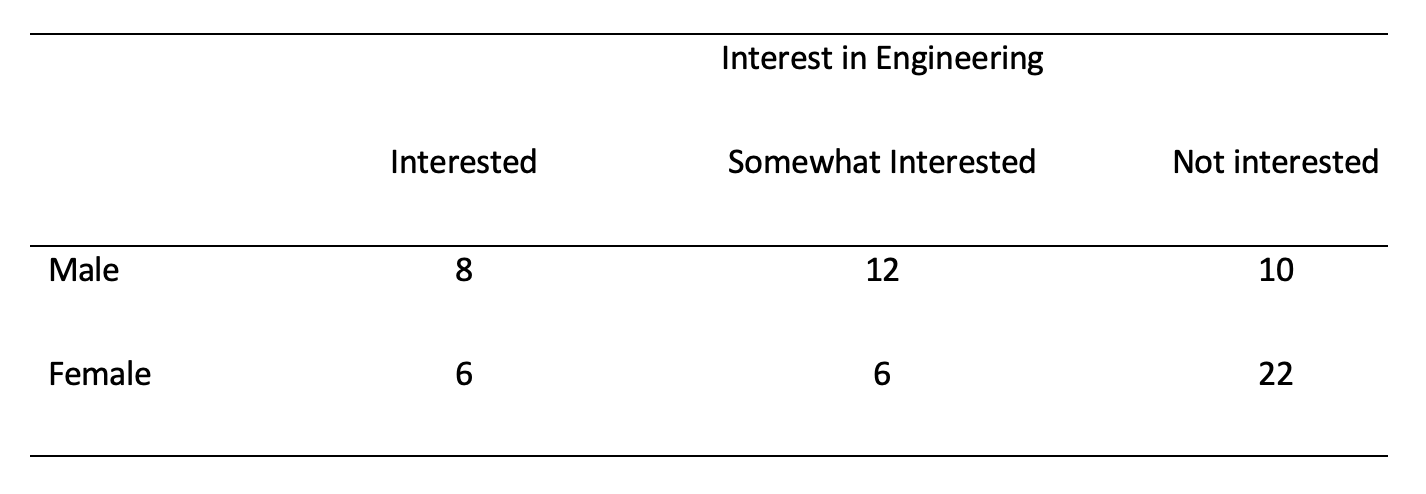

Why is it recommended to opt for multiple 2 x 2 chi-squares instead of chi-squares larger than 2 x 2?

QUESTION 6

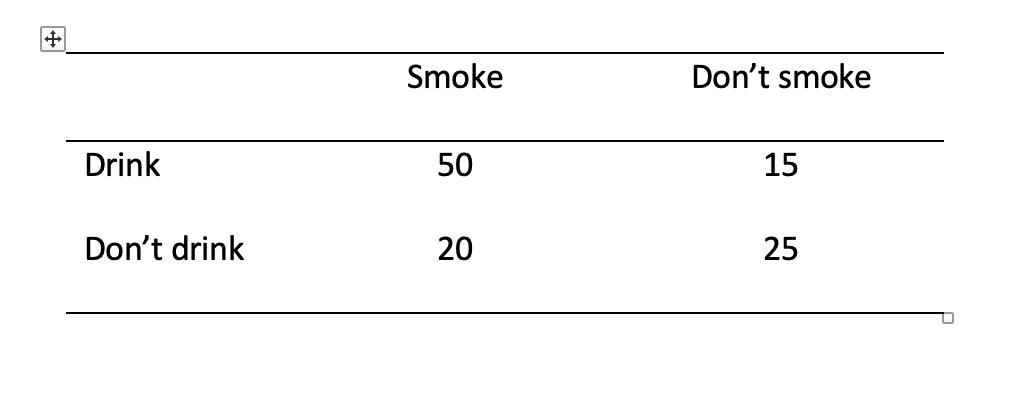

How could you ‘modify’ the contingency table below for chi-square analysis to aid subsequent interpretation of the data/results?

Lab activity 2: Reminders through association

For this lab, we’re going to use data from Rogers, T. & Milkman, K. L. (2016). Reminders through association. Psychological Science, 27, 973-986. You can read the full paper online but the short version is that the authors looked at how people remember to follow through with the intention of doing something.

Although there are lots of potential reasons (e.g., some people may lack the self-control resources), Rogers and Milkman (2016) propose that some people fail to follow through simply because they forget about their good intentions. If this is the case, the authors argue, then having visual reminders to follow through on their intentions may help people remember to keep them. For example, a person may choose to put a sticker for their gym on their car window, so that every time they get in the car they remember to go to the gym.

In Study 1 by Rogers and colleagues, participants took part in an unrelated experiment but at the start of the task they were asked to return a small stack of paper clips to the reception of the building at the end of the study and if they did so the researchers would donate $1 to a charity. They were then asked if they intended to do this. Those in the reminder-through-association (RTA) condition read “Thank you! To remind you to pick up a paper clip, an elephant statuette will be sitting on the counter as you collect your payment.” This message was followed by a picture of the elephant statuette. Those in the control condition simply read “Thank you!”.

What we want to do is to run a chi-square analysis to determine whether those in the RTA condition were more likely to remember to return the paper-clips than those in the control condition.

Let’s put the basics in place:

- Make sure you have started a new R Markdown script. If you need a reminder of how to do that, please revisit week 6 of PSYC121 (here).

- You’ll need the data file

RTA_study1.csvyou downloaded when completing Pre-lab activity 3. If you experienced issues with uploading files to the server, follow the instructions below. - When starting a new analysis, it is a good idea to empty the R environment. This prevents objects and variables from previous analyses interfering with the current one.

- Finally, make sure your working directory is set to the folder in which you have stored the data files (

RTA_study1.csv).

If you experienced difficulties with uploading a folder or a file to the server, you can use the code below to directly download the file you need in this lab activity to the server (instead of first downloading it to you computer and then uploading it to the server). Remember that you can copy the code to your clipboard by clicking on the ‘clipboard’ in the top right corner.

You can clean the R environment by clicking on the broom icon at the top right of the environment window, or you can use the code below.

rm(list=ls())Use the code below to check what you working directory is currently set to. This is the folder that R will use to look for files. Is the file path that is written to the Console after you run the code snippet the one that contains the data file? You can check by nativating to the path you can see in the Console in the ‘Files’ pane on the right. Does it contain the data files?

getwd()If your working directory is not set to the folder that contains the data file, navigate to folder that contains the data file in the ‘Files’ pane, click ‘More’ and then on ‘Set as working directory’.

Step 1. Add the code to load the relevant libraries in a new code chunk. We need the following ones:

lsrandtidyverse. If you are unsure, you can look at the ‘Hint’ below for a clue by expanding it. After that, if you are still unsure, you can view the code by expanding the ‘Code’ section below.

Use the library()function. Remember to put it inside a ‘code chunk’ in your R Markdown script.

The code to do this is below.

library(lsr)

library(tidyverse)Step 2. Read in the data, have a look at the layout of the data and familiarise yourself with it.

Use the read_csv()function to read in the data and the head() function to have a quick look at each data frame.

The code to do this is below.

intent_data <- read_csv("RTA_study1.csv") # Read in the data file

head(intent_data) # Look at the tableIt is a fairly simple data file that contains four variables for 87 participants:

condition: this variable indicates which condition participants were in (1 = reminder-through-association condition, 2 = control condition)intend: this variable indicates whether participants said they were intending to return the paper-clips (1 = yes, 0 = no)actualdonate: this variable indicates whether participants actually ended up returning the paper-clips and therefore donating to charity (1 = yes, 0 = no)id: this variable indicates the participant ID number

Question 2a: What do the numbers in the first row across the four columns refer to?

Step 3. Getting the data ready. We need to do a little bit of wrangling to get our data into the format we need: First, we need to remove all the participants who said that they did not intend to return the paper-clips (intend = 0) as we are only interested in whether people follow through on an intention. Second, to make the output easier to read, we’re going to recode condition to have text labels rather than numerical values.

You can use filter() to remove all participants who said that they did not intend to return the paper-clips. You can use mutate() and recode() to recode the values in condition to make ‘1 = rta’ and ‘2 = control’, and the values in actualdonate to ‘1 = donated’ and ‘0 = no_donation’. Finally, save the output to a new object.

You can do this in two separate steps, or you can use pipes. Also, note that you will need to put both sides of each recode argument (i.e., 1 and rta) in quotation marks, even though 1 and 2 are numbers, they actually represent categories rather than numerical data.

The code to do this is below:

intent_recode <- intent_data %>%

filter(intend == 1) %>%

mutate(condition = recode(condition, "1" = "rta", "2" = "control"),

actualdonate = recode(actualdonate, "1" = "donated", "0" = "no_donation"))

head(intent_recode)Question 3a: How many participants were removed because they didn’t intend to return the paper-clips?

Step 4. Next you need to calculate descriptive statistics. For frequency data these are simply counts so we can use the function

count()rather than having to use thesummarise()function. We want to know how many participants are in each group (rta - donated, rta - didn’t donate, control - donated, control - didn’t donate) so we will need to usegroup_by()to display the results for all combinations ofconditionandactualdonate.

Use the code template below to develop the code. You need to replace the various bits in CAPITALS.

NEW_OBJECT <- DATA_TO_USE %>%

group_by(FIRST_GROUPING_VARIABLE, SECOND_GROUPING_VARIABLE) %>%

count()The code to do this is below:

intent_counts <- intent_recode %>%

group_by(condition, actualdonate) %>%

count()

intent_countsQuestion 4a: How many participants in the control condition didn’t donate?

Question 4b: How many participants in the control condition donated?

Question 4c: How many participants in the rta condition didn’t donate?

Question 4d: How many participants in the rta condition donated?

You may also want to calculate the percentages of participants in each condition. Run this code to do this. Make sure to replace RECODED_DATA with the name of your dataframe in which you have recoded the original data values with string labels (in Step 3).

intent_percent <- intent_recode %>%

group_by(condition, actualdonate) %>%

count() %>%

ungroup() %>% # ungroups the data

group_by(condition) %>% # then groups it again but just by condition

mutate(percent_condition = n/sum(n) * 100)

intent_percentStep 5. Data visualiation. We want to create a simple bar plot of our count data. We’ll use

ggplot()for this in combination with thegeom_bar()function. Use the code template below and make sure to fill in the relevant bits.

ggplot(data = , aes(x = , fill = )) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge")The code to do this is below:

ggplot(data = intent_recode, aes(x = condition, fill = actualdonate)) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge")Question 5a: What does

position = "dodge"do? Remove it and rerun the code to find out.

As you can see, the plot makes it much easier to visualise the data - participants in the RTA condition appear to have been more likely to remember to donate than those in the control condition.

The ggplot2() package allows you to customise all aspects of your plots, so let’s tidy ours up a little bit. We’re going to do the following:

- Edit the labels on the x-axis, y-axis and fill.

- Change the colours of the bars by using

scale_fill_manual()and specifying the colours we want in the values argument - Change the theme of the plot to change how it looks

The code below does this.

TASK Add a comment to each line to indicate what that line does.

ggplot(data = intent_recode, aes(x = condition, fill = actualdonate)) +

geom_bar(position = "dodge") +

scale_x_discrete(name = "Condition", labels = c("Control", "RTA")) +

scale_y_continuous(name = "Count") +

scale_fill_manual(name = "Behaviour", labels = c("Donated", "Did not donate"), values = c("blue", "grey"))+

theme_classic()There are a few things to note about the code we just added on:

- If you use simple colour names then you are restricted in the options you can choose, however, if you want more flexibility you can use hexadecimal colour codes, see here.

- There are multiple themes that you can apply. Have a look at the

ggplot2()cheatsheet for an overview (here. Try out a few and see which one you prefer.

Step 6. Now let’s run that chi-square analysis to see whether our impression from the plot holds up and there is a significant association between the grouping variables.

Use the chisq.test() function. Remember to use the recoded data to make the output easier to read.

The code to do this is below:

results <- chisq.test(x = intent_recode$condition, # the first grouping variable

y = intent_recode$actualdonate, # the second grouping variable

correct = FALSE) # whether we want to apply the continuity correction (use if any of the expected cell frequencies < 10 in 2 x 2 table)

resultsQuestion 6a: What do you conclude from the output?

Step 7. Check the assumptions.

The assumptions for chi-square are as follows:

- The data in the cells should be frequencies, or counts of cases rather than percentages.

- The levels (or categories) of the variables are mutually exclusive. That is, a particular participant fits into one and only one group of each of the variables.

- Each participant may contribute data to one and only one cell. If, for example, the same participants are tested over time such that the comparisons are of the same subjects at Time 1, Time 2, Time 3, etc., then Chi-square may not be used.

- The study groups must be independent. This means that a different test must be used if the two groups are related. For example, a different test must be used if the researcher’s data consists of paired samples, such as in studies in which a parent is paired with his or her child.

- There are 2 variables, and both are measured as categories, usually at the nominal level. While Chi-square has no rule about limiting the number of cells (by limiting the number of categories for each variable), a very large number of cells (over 20) can make it difficult to meet assumption #6 below, and to interpret the meaning of the results.

- The expected cell frequencies should be greater than 5.

Assumptions 1) to 5) should be evaluated by reviewing the design of the study. The only assumption that we need to check with R is whether all expected frequencies are greater than 5.

TASK Write the code to check that all expected frequencies are greater than 5.

The information we need is in the object in which your stored the results of the Chi-square test.

The code to do this is below:

results$expectedQuestion 7a: What do you conclude from the output?

Step 8. The last step before writing up the results is to calculate an effect size so that we have a standardised measure of how large the association between our grouping variables is, the effect size measure for chi-square is Cramer’s V. To calculate Cramer’s V we’re going to use the function

cramersv()from thelsrpackage. The code mirrors the code used for the Chi-square test itself:

eff_size <- cramersV(x = intent_recode$condition, # the first grouping variable

y = intent_recode$actualdonate, # the second grouping variable

correct = FALSE) # whether we want to apply the continuity correction (use if any of the expected cell frequencies < 10 in 2 x 2 table)

eff_sizeWe can square the effect size (or multiple it by itself) to see how much variance in one variable is accounted for by the other variable. Use the code snippet below to square the effect size.

percentageAccountedFor <- eff_size * eff_size *100

percentageAccountedForQuestion 8a: How large is the effect and how much variance is accounted for?

Step 9. To help with interpreting the relationships, it is useful to look at the standardised residuals. These are z-scores that indicate how many standard deviations above or below the expected count, an observed count is (thus indicating how much they differ). Remember, for z-scores the following holds: +/- 1.96, p <.05, +/- 2.58 p <.01, +/-3.29 p < .001

results$residuals # check the standardised residualsQuestion 9a: What do you conclude from the output?

Step 10. Write up the results following APA guidelines.

The Purdue writing lab website is helpful for guidance on punctuating statistics.

Answers

When you have completed all of the lab content, you may want to check your answers with our completed version of the script for this week. Remember, looking at this script (studying/revising it) does not replace the process of working through the lab activities, trying them out for yourself, getting stuck, asking questions, finding solutions, adding your own comments, etc. Actively engaging with the material is the way to learn these analysis skills, not by looking at someone else’s completed code…

Lab activity 1

- How does Pearson’s Chi-square differ from Pearson’s correlation?

- Chi-square test of independence would be appropriate when testing the following questions:

- What is the relationship between gender and soft drink preference?

- How do males and females compare in terms of wanting to be a psychologist when they leave school?

- Write the chi-square formula below.

- What were your answers to the pre-lab activity 1 questions? Please compare them with other students at your table. Complete the Pearson’s chi-square test by hand using the data above and fill in the blanks:

- Why is it recommended to opt for multiple 2 x 2 chi-squares instead of chi-squares larger than 2 x 2?

- How could you ‘modify’ the contingency table below for chi-square analysis to aid subsequent interpretation of the data/results?

Lab activity 2

Question 2a: What do the numbers in the first row across the four columns refer to?

Question 3a: How many participants were removed because they didn’t intend to return the paper-clips?

Question 4a: How many participants in the control condition didn’t donate?

Question 4b: How many participants in the control condition donated?

Question 4c: How many participants in the rta condition didn’t donate?

Question 4d: How many participants in the rta condition donated?

Question 5a: What does

position = "dodge"do?

Question 6a: What do you conclude from the output?

Question 7a: What do you conclude from the output?

Question 8a: How large is the effect and how much variance is accounted for?

Question 9a: What do you conclude from the output?

Write up:

Online Q&A

Below is the recording of this week’s online Q&A.