library(tidyverse) # allows pipes, arrang(), summary(), aov(), etc

library(rstatix) # allows group_by()

library(effectsize) # a neat little package that provides the effect size

library(ggpubr) # allows us to examine QQ Plots3. Assumptions of ANOVA and Follow-Up Procedures

Sam Russell, Mark Hurlstone

Lab

Welcome back to Lab 3 of Year 2 Stats!

It’s that wonderful time of the week again - a time to tango with R studio. As with preceding weeks, we will be working from an activity sheet, which outlines a number of decent tasks to complete in R Studio. The objectives of today’s lab are three fold:

- Running tests of the assumptions of ANOVA.

- Run and report planned comparisons and post-hoc tests - You choose which ;)

- Debug code which isn’t doing the business.

As always, myself (Sam Russell, weeks 1-4), Mark Hurlstone (weeks 5-9) and an apt team of GTAs will be circulating through the room and answering any queries you may have. In Psyc214, we also encourage peer engagement and joined problem solving - so please do not hesitate to ask for help from another on your table or to work together in small groups. Right, that enough for now, so let’s get started!💪

1 - General Introduction to Lab 3

“It does not matter how slowly you go, as long as you do not stop.” | Confucius.

Confucius

1.1 Access to R Studio

To log in to the R server, first make sure that you have the VPN switched on, or you will need to be connected to the university network (Eduroam). To set up the VPN, follow ISS instructions here or connecting to Eduroam here.

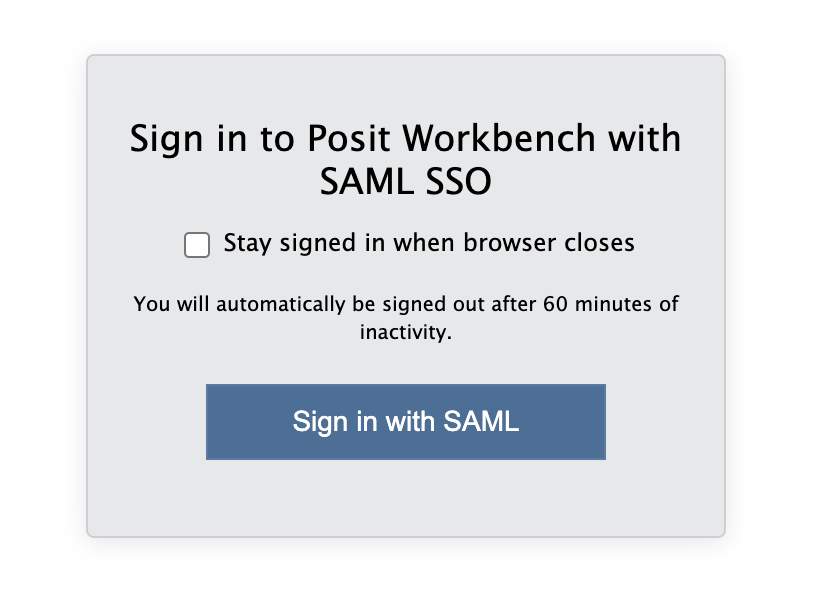

When you are connected, navigate to https://psy-rstudio.lancaster.ac.uk, where you will be shown a login screen that looks like the below. Click the option that says “Sign in with SAML”.

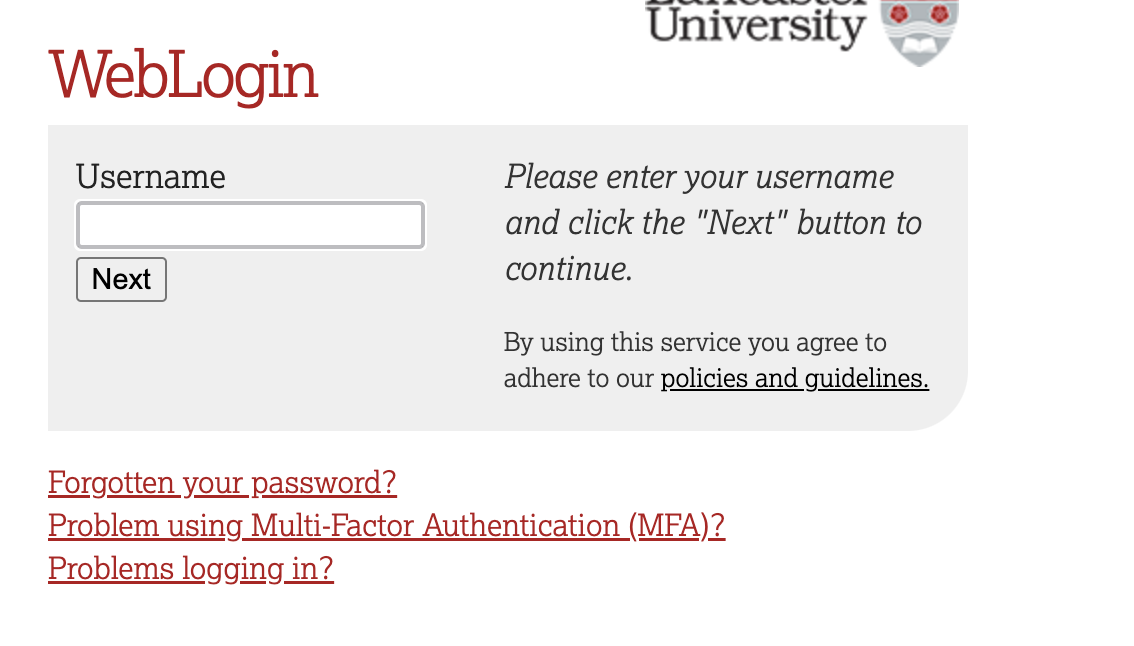

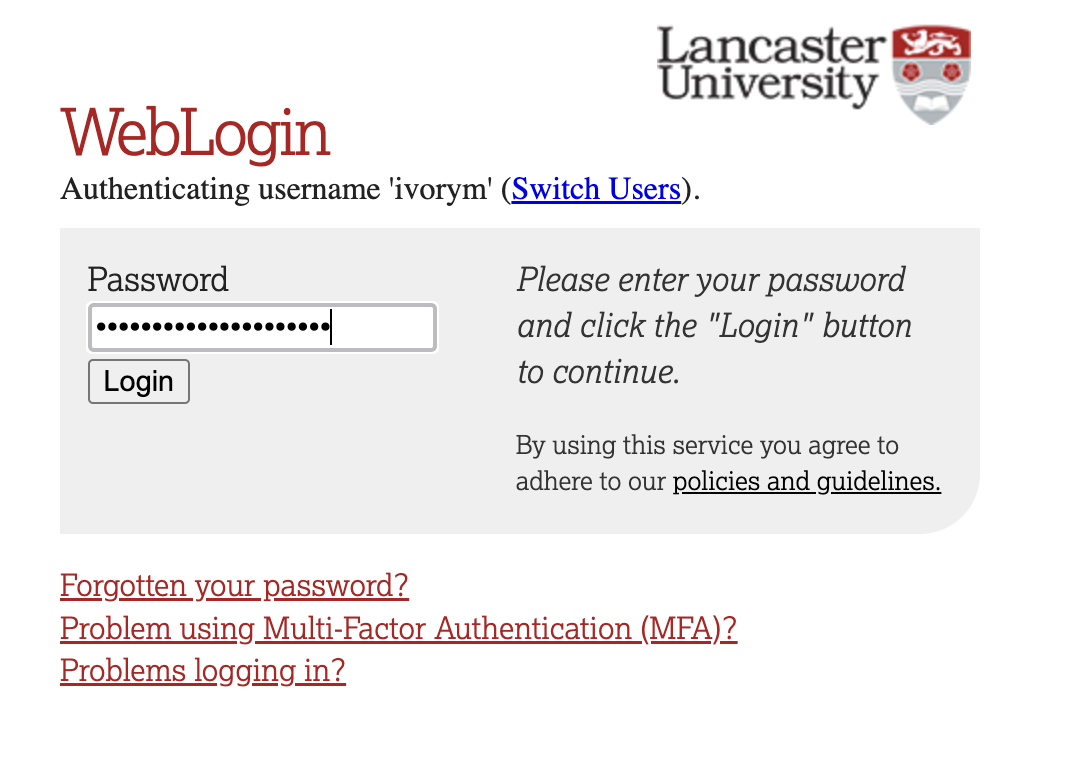

This will take you through to the University login screen, where you should enter your username (e.g. ivorym) and then your university password. This will then redirect you to the R server where you can start using RStudio!

If you have already logged in through the university login already, perhaps to get to the portal, then you may not see the username/password screen. When you click login, you will be redirected straight to RStudio. This is because the server shares the login information securely across the university.

1.2 Loading the packages (dependencies) and loading the data set

Lovely stuff. Here we are, up in the server clouds of R Studio - a plain of statistical delight.

Similar to last week, we first need to access the dataset. To access today’s dataset, we first just need to download it from Moodle.

Step 1. Please ensure that you download today’s data from the Psyc214 week 3 ‘lab’ folder in Moodle. Please download the week3_robo_lab.csv file from here.

Now that you have the data saved on your machine, we next need to make a space on our own individual R Studio servers in which to house the data. Like last week, to do this, we first need to create a folder. On the server, please navigate to the bottom right panel (see figure below). Here, under the ‘files’ you will see the option to add ‘New Folder’. Click on this and name the new folder psyc214_lab_3 Note. This needs to be spelled correctly and we need to make sure we that we specify this is lab_3! We are so over lab_1 and lab_2 that it’s not even funny.

Now that you have a folder in waiting, it’s time to add week 3’s data file. To upload today’s week3_robo_lab.csv file into this folder, please open your new psyc214_lab_3 folder. When in the new folder, select the ‘Upload’ tab (see figure below). This will present a box that will ask where the data is that you want to upload. Click on “Browse…”, find where you have the week3_robo_lab.csv data file on your computer and click ‘OK’

Perfect! The data is now sat in its slippers and dressing gown on your own R Studio server, waiting to be called upon.

STOPPPPPPPPP!!!!! We’ll want to be able to save this session on our server: to do so please: click ‘File’ on the top ribbon -> New project. Next, select existing directory and name the working directory ~/psyc214_lab_3 -> hit ‘create project’

STOPPPPPP!!!!! Please ensure you have created a script and you are working in this script - top left of the pane of the R Studio Server. This will make it easier for you to return to your code at a later date. To do this, please click ‘File’ -> ‘New file’ -> ‘Create new R script’

This will now create a project and script file in this week’s R Studio Server lab 3 folder where it will save your progress! You can then return to this at a later date - likely close to the exam wink wink

As always, we should start our new session by loading the packages (i.e., the dependencies) we’ll use for this session.

Please copy or type the following commands into R Studio to get these packages activated:

More on these packages later.

Ok - Time to load the data and roll on today’s work.

- First we need to set the working directory to ‘psyc214_lab_3’, i.e., tell R Studio the location in which today’s data sits, waiting and lurking. To recap, the working directory is the default location or folder on your computer or server by which R will read/save any files.

The working directory can be set with the following R code:

setwd("~/psyc214_lab_3")- Now the have the directory set up, let’s type the command to read the housed data.

lab3_data <- read_csv("week3_robo_lab.csv")where ‘lab3_data’ is the name we’ve assigned that R will recognise when it calls up our data, ‘read_csv’ is the R tidyverse command to pull up the data and “week3_robo_lab.csv” is the name of the data file stored on the server.

# Set condition to a factor with 3 levels: A, B, O

lab3_data$Group = factor(lab3_data$Group, levels = c("A","B","O"))2 - Today’s lab activities

With the working directory set, the data loaded and the packages called, it is now time to have a play.

2.1 Some background information about the dataset

We are now all well versed in the mad goings on at Lancaster University Psychology Department. The crazy cats there wanted to examine whether Psyc214 students would respond well to an ambitious initiative which would introduce synthetic robots as stats lab assistants. This began with the creation and assessment of two robots (Robot A[lpha] and B[eta]). Applying a between-participants design, the researchers found that those students assigned Robot B(eta) rated their robot as significantly more likable than those assigned Robot A(lpha). Furthermore, Robot B(eta) students did significantly better overall in their Psyc214 exam.

A grumpy reviewer, however, suggested the research was flawed, as it did not include a third, more realistic robot. Citing the ‘uncanny valley’ phenomenon, this reviewer expected that a more realistic looking robot would be less likable and that its assigned students would do significantly poorer in their Psyc214 assessments. The researchers set out to satisfy this reviewer and developed a third robot. Unlike the reviewer, however, the researchers expected that the most realistic robot would receive both the highest likeability scores and Psych214 assessment scores. The research team expected the following:

Likeability attitudes towards a participant’s robot would be significantly higher for individuals assigned Robot O(mega) than those assigned Robot A(lpha) or B(eta) (Hypothesis 1)

Psyc214 assessment scores would be significantly higher amongst individuals assigned Robot O(mega) than those assigned Robot A(lpha) or B(eta) (Hypothesis 2)

Last week, in our lab, we ran a one-factor between-participants ANOVA and found that our three groups statistically differed: both in their perceptions of how likeable their assigned robot was, but also in their achievement scores for the Psyc214 assessment. What we’ve learned in our lectures, however, is that while an ANOVA can detect likely statistical differences between groups, it cannot pinpoint specifically which groups varied from another. Is it Alpha and Beta? Or Alpha and Omega? Or Beta and Omega? Questions remain…

2.2 Refamiliarizing with our data

Just for a recap, let’s open our data and look at the top 50 data points:

Full disclaimer, from this point on, we will start to include some bugs in code which you will need to resolve. Wicked of us, I know, but it is important that you are able to engage with the code and correct it when needs be. Myself (Sam) and Mark H have more experience in R than yourselves, but still frequently and inadvertently write funky code that requires us to go back and work through our (il)logic - it’s a fact of coding life that never goes away.

[The frustration of debugging!]https://images.pexels.com/photos/2868257/pexels-photo-2868257.jpeg?auto=compress&cs=tinysrgb&dpr=2&h=750&w=1260)

Please call up the data using the head() function, and ask for the top 50 data points.

head(lab3 data, n = x)What a piece of work these lecturers are. For some reason this code is buggy. Try to figure out what went wrong and how you can correct it. hint, it’s something with the data name and number of data points being called.

Because of the way we ordered our data in the original .csv spreadsheet, we are not able to see beyond the first 50 cases in Group A. Therefore, let’s use the arrange() function to order our data instead by Score, highest first - we can combine this with the head() through the use of a pipe %>%. Please recall, a pipe works as a specialized chain, letting you pass an intermediate result onto the next function.

lab3_data %>% arrange(Score) %>% head(n=50)# A tibble: 50 × 4

ID Group Likeability Score

<dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 112 B 4 40

2 34 A 3 44

3 159 B 4 44

4 50 A 2 46

5 68 A 2 46

6 104 B 2 46

7 160 B 5 46

8 20 A 3 47

9 106 B 3 47

10 186 O 1 47

# ℹ 40 more rowsThis is great. Well, kind of. The order is the wrong way round!? i.e., it’s ordered from lowest to highest - this will never do. Let’s have another try using the (desc(VARIABLE). If you struggle, please ask for help.

OK - now let’s do the same and check the 50 highest Likeability values. To do this, please use the same successful code as above, but change ‘Score’ to ‘Likeability’

# ANSWER CODE

lab3_data %>% arrange(desc(Likeability)) %>% head(n=50)# A tibble: 50 × 4

ID Group Likeability Score

<dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 238 O 33 63

2 126 B 7 50

3 83 B 6 53

4 94 B 6 72

5 99 B 6 64

6 108 B 6 70

7 115 B 6 64

8 116 B 6 60

9 123 B 6 63

10 129 B 6 60

# ℹ 40 more rowsIf done correctly you will receive the following output

# A tibble: 50 × 4

ID Group Likeability Score

<dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 238 O 33 63

2 126 B 7 50

3 83 B 6 53

4 94 B 6 72

5 99 B 6 64

6 108 B 6 70

7 115 B 6 64

8 116 B 6 60

9 123 B 6 63

10 129 B 6 60

# ℹ 40 more rowsNow wait! We almost forgot! Our data is a tad on the dodgy side. We can see that the highest likeability score was 33. This can’t be right? Can it?! Nope, definitely not, the scale should range from 1 - 7, meaning this is an error.

Let’s straighten this out, post haste. To do this, please type or copy/paste the following command

lab3data$likeability[lab3_data$Likeability > 7] <- NA # sets any Likeability value over 7 to missingYou’ve got to be kidding me! Yet another bug in the code? Well, I guess it’s up to us to roll up our sleeves and sort out this mess.

Please try to correct the code and get this sorted. hint, there seems to be something funky going on with the name of the data variable and the DV.

This is asking R Studio to scan the likeability column of our dataset and to set any value above 7 as missing.

Now let’s check out the top 3 likeability scores again, just to be sure the 33 has gone.

lab3_data %>% arrange(desc(Likeability)) %>% head(n=3)# A tibble: 3 × 4

ID Group Likeability Score

<dbl> <fct> <dbl> <dbl>

1 126 B 7 50

2 83 B 6 53

3 94 B 6 72No nasty tricks this time. Everything looks good.

Let’s now use the rstatix() package to get some neat and tidy summary statistics.

We first specify the dataset we will use - which is lab3_data. After this we will use a pipe to ask R Studio to pass this data set on to the next function. Here, we use the group_by() function to specify that we want to distinguish between our three different groups - a variable conveniently named ‘Group’. We then use another pipe to pass the intermediate result onto the next function - the get_summary_stats(). In the parentheses we include our two DVs ‘Likeability’ and ‘Score’. Finally we are asked to specify what ‘type’ of summary statistic we would like. Let’s go for mean, standard deviation, min and max values.

Descriptives = lab3_data %>%

group_by(Group) %>%

get_summary_stats(Likeability, Score, show = c("mean", "sd", "min", "max"))

options(digits = 3)

print.data.frame(Descriptives) Group variable n mean sd min max

1 A Likeability 80 2.50 0.928 1 4

2 A Score 80 58.10 6.449 44 72

3 B Likeability 80 4.50 1.006 2 7

4 B Score 80 60.36 7.266 40 74

5 O Likeability 79 2.11 0.847 1 4

6 O Score 80 63.60 7.217 47 79Ok, perfect. This reminds us of a lot of vital information. For example, we can see that the mean Likeability scores for Groups A, B, O are 2.5, 4.5, 2.11, respectively.

Something we don’t have, however, is the median, which is denoted as “median”. Repeat the code above, but now also include in the c() the “median”. Hint, don’t forget the comma.

3 - One-factor between group ANOVA

3.1 Assumptions

Ok. Enough dilly dallying. It is time to re-run our one-factor between group ANOVA and to check that we were not daydreaming last week - there were actually statistical differences between our robot groups on both the Likeability scores and the Psyc214 assessment scores.

Before we embark on that adventure, however, it is good practice to test the assumptions of ANOVA, to ensure that we are not violating expectations of data and that a parametric test is, indeed, suitable.

As you will recall from Lecture 3, there are 3 key assumptions of ANOVA.

1) The assumption of independence (i.e., are our data points unique? - let’s say ‘yes!’)

2) The assumption of normality (i.e., are our groups showing normal distributions with their data points?)

3) The assumption of homogeneity of variance #mouthful (i.e., is the variance in data points similar for all groups?)

The first one - assumption of independence - we need to search our souls and ask if this is the case. Let’s say “yes, yes it was”.

The other two - assumption of normality and homogeneity variance - we can test by analytical means.

Let’s give it a go! (To be fair, we should have done this last time before running our ANOVA in the first place!)

We should also check if are there any extreme values in our data - remember Lecture 3. These extreme values can come from data entry errors (like with the 33), measurement errors or be unusual values. Extreme values can seriously impact the conclusions we can make about our data.

3.1.1 Extreme values

We can eye ball boxplots to look for suspicious data points, or we can test for extreme values very easily using the rstatix() package. It has this wonderful function called identify_outliers(), which will tell us if we have any outliers or extreme values. As a rule, outliers are typically fine to work with, extremes however are when things become a bit hairy.

Please copy the following code:

lab3_data %>%

group_by(Group) %>%

identify_outliers(Likeability)# the function to identify outliers and extreme values# A tibble: 2 × 6

Group ID Likeability Score is.outlier is.extreme

<fct> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <lgl> <lgl>

1 B 104 2 46 TRUE FALSE

2 B 126 7 50 TRUE FALSE Great. This has told us that we have a couple of ‘TRUE’ outlier values (participants 104 and 126) for Group B(eta), but no extremes (denoted by ‘FALSE’), so we can relax.

Now please reproduce the code above, but ask R Studio whether there are any outliers for our ‘Score’ variable:

Again we have a value from the B(eta) group which is an outlier away from the others (participant 112) - but no extremes. We can relax again!

3.1.2 Assumption of Normality

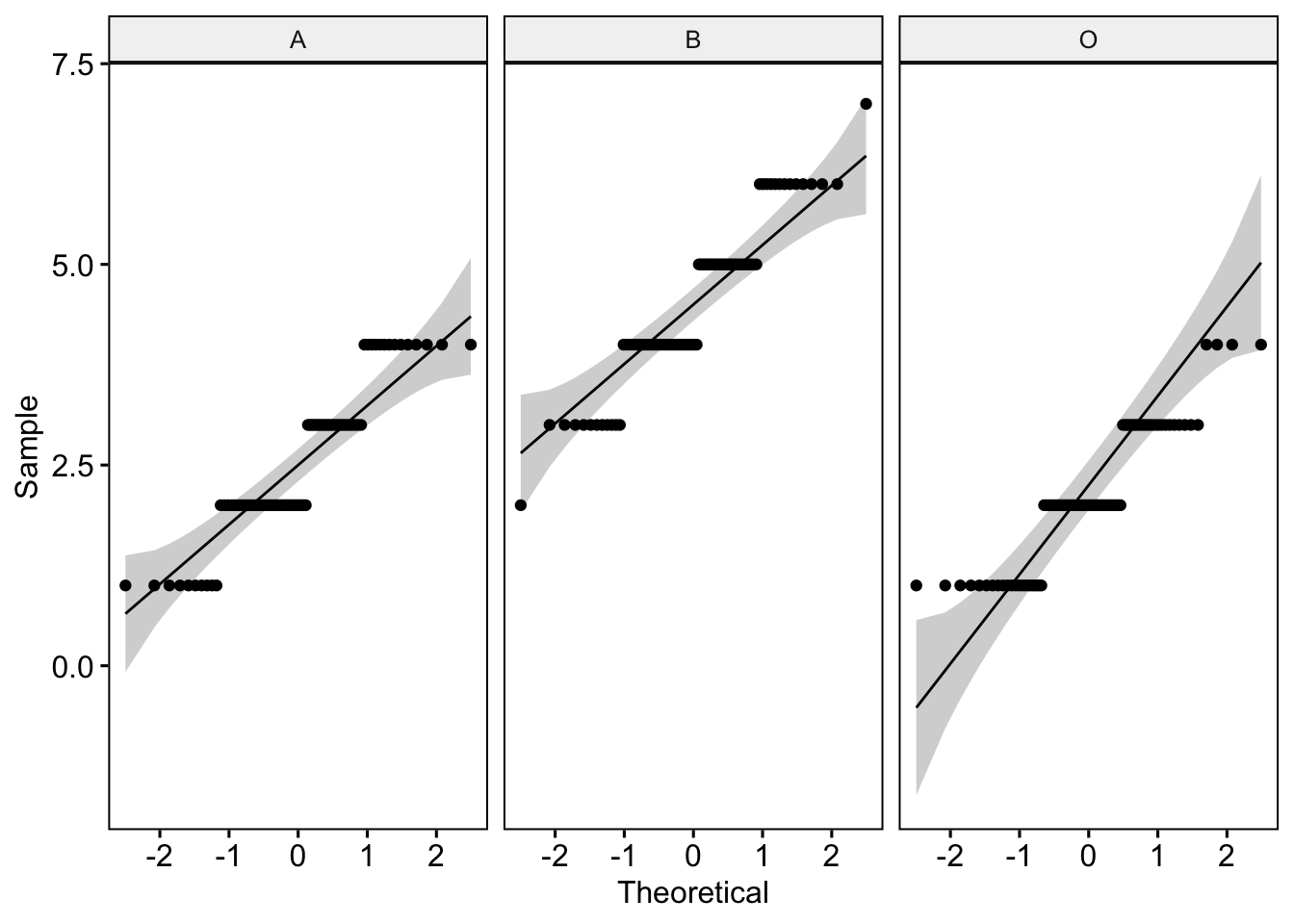

We can test whether our data are normal using QQ plots and a Shapiro-Wilk test of normality. The QQ plot maps out the correlation between our data and a normal distribution. If many data points fall away from our reference line and outside the band of the 95% confidence interval we can assume that data are non-normal.

The Shapiro-Wilk test statistically calculates whether our data are ‘normal’. If the p-value for our Shapiro-Wilk statistic is equal to or less than p = .05, then this indicates we have failed the test and have non-normal data - not good! The Shapiro-Wilk test, however, becomes less useful as we have a larger N. The larger the sample, the more likely it is that you will get a statistically significant Shapiro-Wilk test result and our data will be assumed to be non-normal.

As we have a large data set (N = 239), we will ignore the Shapiro-Wilk statistic for now and only focus on the QQ plot.

We will use the ggpubr package to generate our QQ plot. Let’s start by looking at the ‘Likeability’ values:

ggqqplot(lab3_data, "Likeability", facet.by = "Group") # where we use "" around our variable names

The plot generated shows how our data correlate to the normal distribution. As we have many data points away from the reference line, we should be concerned that these data are not normal.

Let’s run a Shapiro-Wilk test too and see what it tells us:

lab3_data %>%

group_by(Group) %>%

shapiro_test(Likeability)# A tibble: 3 × 4

Group variable statistic p

<fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 A Likeability 0.869 0.000000744

2 B Likeability 0.913 0.0000433

3 O Likeability 0.859 0.000000386Oh dear. All of our groups have highly significant Shapiro-Wilk test statistics. This is further evidence our Likeability data are not normal!

We have options. We can either transform the data (see lecture 3) and analyze the transformed data using the ANOVA. Or, we can accept the data are non-normal and run a non-parametric alternative - i.e., the Kruskall-Wallace one-way Analysis of Variance by Ranks. In the interest of brevity, we will leave this for another day. From this point on today, let’s park the ‘Likeability’ variable and focus soley on the ‘Score’ variable

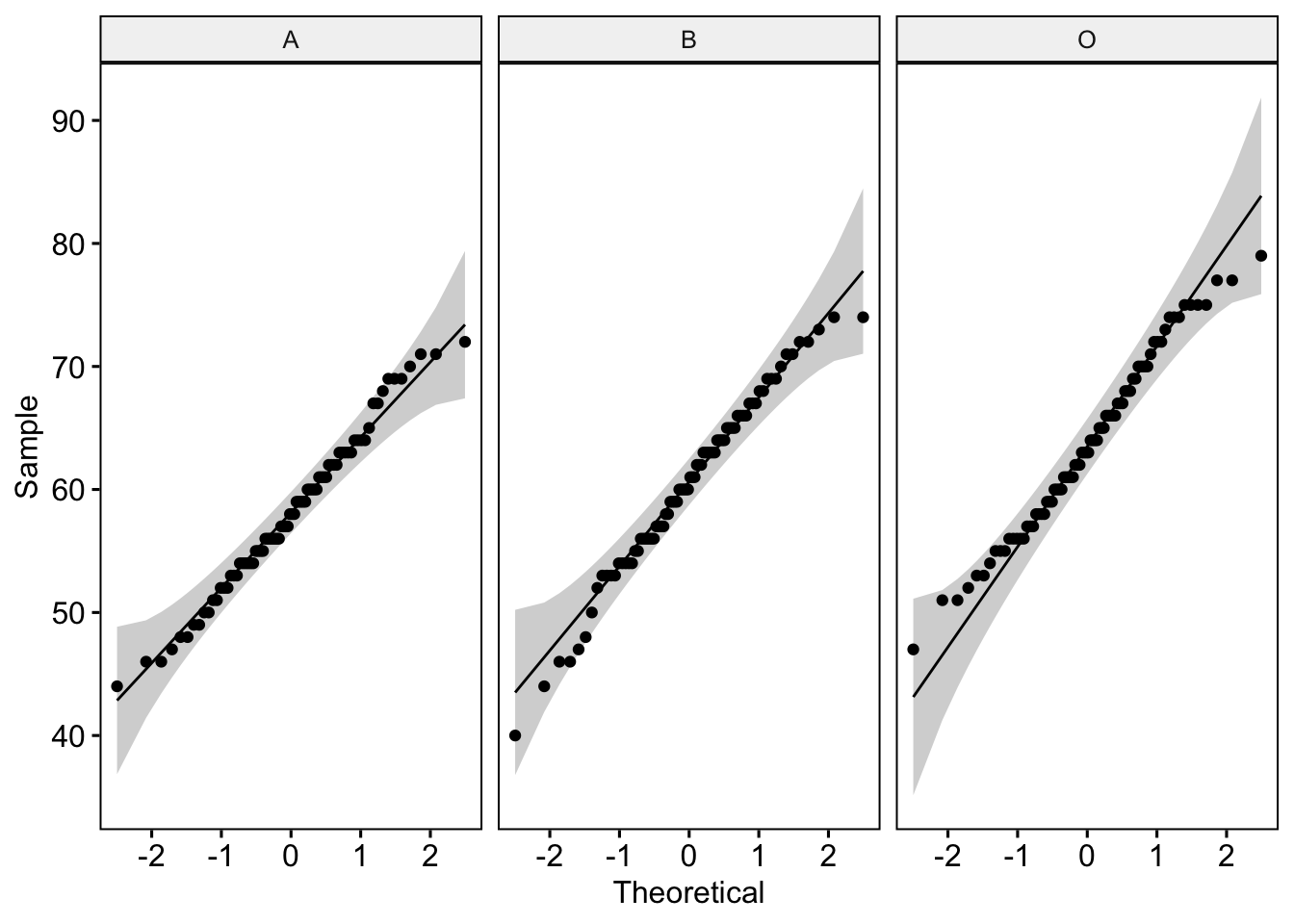

Now please run both the QQ plot code and Shapiro-Wilk test code for our ‘Score’ variable.

#ANSWER CODE

ggqqplot(lab3_data, "Score", facet.by = "Group")

#ANSWER CODE

lab3_data %>%

group_by(Group) %>%

shapiro_test(Score)# A tibble: 3 × 4

Group variable statistic p

<fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 A Score 0.987 0.589

2 B Score 0.984 0.418

3 O Score 0.984 0.430If run correctly, you should get the following.

# A tibble: 3 × 4

Group variable statistic p

<fct> <chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 A Score 0.987 0.589

2 B Score 0.984 0.418

3 O Score 0.984 0.430Now these don’t look too shabby at all. For the QQ plot, our data points lie close to the reference line - this is good news. Further, the Shapiro-Wilk statistic is non-significant - another good sign. We can be pretty confident that our ‘Score’ data are normal.

The Score variable moves on and we still may have a chance to analyze it with an ANOVA

3.1.3 Assumption of Homogeniety of Variance.

Before we carry out our ANOVA, we need to make sure that our ‘Score’ variable also meets the assumption of homogeneity of variance. We can test whether our three samples have equal variances using the Levene Test for Equality of Variances. If we find the p-value is > 0.05, aka non-significant, we can be relatively confident that there are no significant difference in variances across groups.

Let’s give it a whirl with the ‘Score’ variable.

lab3_data %>% levene_test(Score ~ Group)# A tibble: 1 × 4

df1 df2 statistic p

<int> <int> <dbl> <dbl>

1 2 237 0.799 0.451We have a non-significant p-value. This is a good sign! This means that the variance for our groups are roughly equal.

3.2 Running a one-factor between group ANOVA

Phew. Now that’s all over and we’re legit - well for the ‘Score’ variable at least, it’s time to run our one-factor between participants ANOVA. Like last week, we will use tidyverse’s ‘aov()’ function. Let’s set ‘Score’ as our dependent variable of examination. ‘Group’ is then our predictive factor (independent variable). Note, in the code below, the DV and the IV are separated by the ‘~’ character. Please carry out the following command. This also includes requesting a summary and effectsize for our model.

Model_1 - aov(data = lab3_data, score ~ group) # We name our overarching model Model_1

print(summary(Model_1), digits = 5) # We print a summary of this model. This provides F statistic and P value. Change the number of digits to alter the number of displayed decimal places.

effectsize(Model_1) # We ask for an eta2 effect size for our modelOh blast. What an evil web of deceit we weave. The code again appears to have bugs in it - something which incidentally and thematically fits well with ‘webs’.

There is something not working in this code. Let’s take it slow, working from top to the bottom. Essentially, if Model_1 is not well specified, all other commands involving this Mode1_1 construction will fail. Please try to correct the code.

This has provided us with a whole bunch of useful information! It shows us the between group variability value (do you remember, the numerator value in our F ratio equation from lecture 2?), which R has named the Group Mean Square (a value here of 611.30).

It also provides the within group variability value - aka the error term (do you remember, the denominator in our F ratio equation from lecture 2), which R has named the Residuals mean square (a value here of 48.80)

It provides the crucial F-ratio statistic, here a value of 12.52.

The output also shows an Eta-squared (η2) effect size of 0.10. As a rule of thumb, η2 = 0.01 indicates a small effect; η2 = 0.06 indicates a medium effect; η2 = 0.14 indicates a large effect. Our eta-squared (η2) represents a medium effect - i.e., our experimental manipulation had a moderate effect on student Psyc214 test scores.

3.3 Reporting the results of the one-factor between-participants ANOVA in APA format

All results should be written up in accordance with the American Psychological Association’s (APA) guidance. This ensures that your results are easy to interpret and that all the relevant information is present for those wishing to review/replicate your work.

The current results can be reported as following: “A one-factor between-participants ANOVA revealed that Psyc214 scores were significantly different between our robot groups (Robot A M = 58.10, SD = 6.45; Robot B M = 60.40, SD = 7.27; Robot O M = 63.60, SD = 7.22), F(2,237) = 12.52, p < .001, η2 = 0.10, 95% CI[0.04, 1.00].

*Hold up!!! While the ANOVA tells us that there are differences between groups, it doesn’t tell us specifically which groups differ from one another. For example do Group A and B statistically differ? A and O? B and O? The only way to know this definitively is to carry out posthoc/planned contrast tests**

3.4 Decisions, decisions, decisions…

Just to recall, from lecture 3, following an ANOVA, we need to further scrutinize the differences between our separate groups.

This can be done in one of three ways. 1) T-tests with no adjustments (let’s ignore this one, because it is just bonkers - please refer to lecture 3 if unsure why) 2) Planned comparisons of specific relationships with adjusted p-values (e.g., Bonferroni corrections) 3) Post-hoc tests (e.g., Tukey HSD) which are interested in differences between all possible combinations of groups and also have conservative p values.

To recap, as a rule of thumb, planned comparisons are always preferable. But these entail that you have a pre-specified idea of which groups should differ.

We’re not going to make this decision for you. Please choose whether you would like to run a:

i) planned comparison test in which we compare one or two pairs of specific groups of interest (number of levels minus 1 - i.e., we can run up to two comparison tests).

ii) post hoc tests where we are interested in statistical differences between all possible combinations of groups.

Take your pick now. If you’re an advocate for the ‘Planned Comparisons’ please skip to section 3.5 and ignore 3.6 for now. If you’re an advocate of ‘Post hoc tests’ please skip to section 3.6 and ignore 3.5 for now

3.5 Planned comparisons

Oh hello, and welcome. I can see you’ve gone for the planned comparisons - i.e., you have an idea which specific groups should differ and want to see that through.

Let’s run a between-groups pairwise t-test with Bonferroni correction. Note, to get an adjusted p value with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, we need to be sure that we include p.adjust.method = “bonferroni. If we do not add this line of code then we will just get regular p-values without the conservative adjustment.

Let’s only compare the scores for Omega versus Alpha and Omega versus Beta:

lab3_data %>%

# Execute independent-samples t-tests - remember to set pool.sd = FALSE, and include Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparions

pairwise_t_test(Score ~ Group, pool.sd = FALSE, var.equal = TRUE, p.adjust.method = "bonferroni",

# Just generate the two comparisons of interest: e.g., Omega vs. Alpha # and Omega vs. Beta

comparisons = list(c("O","A"), c("O","A")))# A tibble: 2 × 10

.y. group1 group2 n1 n2 statistic df p p.adj p.adj.signif

* <chr> <chr> <chr> <int> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr>

1 Score A O 80 80 -5.08 158 1.04e-6 2.08e-6 ****

2 Score A O 80 80 -5.08 158 1.04e-6 2.08e-6 **** Oh blast, there’s an error in our code as we seem to have compared Omega versus Alpha twice! Try to adjust your code to ensure you also compare Omega versus Alpha.

We would now add this information in our APA write up. Make sure when you interpret and write up the output that you report the adjusted p-value (i.e., ‘p.adj’ in the output), as opposed to the non-adjusted and dicey p value (i.e., ‘p’ in the output).

We also want to generate some effect sizes for these pairwise comparisons. This can be done using the rstatix’s cohens_d() function.

# Cohen's d effect size for O vs. A

OvsA_d <- cohens_d(lab3_data$Score[lab3_data$Group == "O"],lab3_data$Score[lab3_data$Group == "A"])Fantastic. This tells us that our pairwise comparison for the O and A groups has a Cohen’s D effect size of 0.80.

Now try your own code out to generate an effect size for groups O and B.

The current results can be reported as following: “A one-factor between-participants ANOVA revealed that Psyc214 scores were significantly different between our robot groups (Robot A, M = 58.10, SD = 6.45; Robot B, M = 60.40, SD = 7.27; Robot O, M = 63.60, SD = 7.22), F(2,237) = 12.52, p < .001, η2 = 0.10, 95% CI[0.04, 1.00]. Planned comparisons with Bonferroni adjustments, found that students who were assigned Robot A and B had significantly lower Psyc214 scores than those assigned Robot O, t(156) = -5.08, p < .001, d = .80 and t(158) = -2.83, p = 0.011, d = .45, respectively.”

Note, we didn’t report all combinations. Given our hypotheses, we were interested in Omega. Therefore, we did not need to look at the combination of Alpha and Beta.

3.6 Post hoc tests

Oh hello, and welcome. I can see that you’re more of a post hoc kind of individual - i.e., you haven’t got any specific idea of which groups should differ or are just plain nosy and would like to examine all possible combinations of group differences.

We will run a Tukey-Kramer HSD test. This was covered in Lecture 3 - but fortunately, we will not need to get out our Tukey Studentized Range Statistic table and line up the values by hand - R will do this all for us (lovely, generous R)

Ok, so let’s enter the posthoc command:

lab3_data %>% tukey_hsd(Score ~ Group) # where tukey_hsd is our post-hoc test of choice# A tibble: 3 × 9

term group1 group2 null.value estimate conf.low conf.high p.adj

* <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 Group A B 0 2.26 -0.343 4.87 0.103

2 Group A O 0 5.50 2.89 8.11 0.00000369

3 Group B O 0 3.24 0.632 5.84 0.0103

# ℹ 1 more variable: p.adj.signif <chr>Please look at the output. It compares groups A and B, A and O, B and O. The p-values are adjusted to be conservative, to try and combat the vulnerability of familywise type I error:

A and B, p = 0.103

A and O, p = 0.00000369

B and O, p = 0.0103

The posthoc results show that there is no statistical difference in scores between groups A and B. A and O are highly significantly different from one another, while B and O are statistically significantly different at a of p = 0.01.

We can generate effect sizes for each combination using the cohens_d() function from rstatix.

The following code produces the first Cohen’s d effect size for the comparison of group A and B:

# Cohen's d effect size for A vs. B

AvsO_d <- cohens_d(lab3_data$Score[lab3_data$Group == "A"],lab3_data$Score[lab3_data$Group == "B"])Now try your own code to generate a Cohen’s d statistic for A and O; B and O:

The current results can be reported as following: “A one-factor between-participants ANOVA revealed that Psyc214 scores were significantly different between our robot groups (Robot A, M = 58.10, SD = 6.45; Robot B, M = 60.40, SD = 7.27; Robot O, M = 63.60, SD = 7.22), F(2,237) = 12.52, p < .001, η2 = 0.10, 95% CI[0.04, 1.00]. Tukey-Kramer HSD posthoc tests showed that the difference in students’ test scores (5.50) between participants assigned Robot A and Robot O was statistically significant (adjusted p < 0.001, d = -0.80). The difference in students’ test scores (3.24) between participants assigned Robot B and Robot O was statistically significant (adjusted p = .01, d = -0.45), but there was no statistical group difference between Robot A and B (2.26, adjusted p = 0.10, d = -0.33).”

Now that you’ve finished this. Please go on to ‘4 Further tasks’.

4 Further tasks

Well done for completing what has been the most difficult lab week thus far. Regardless of your allegiance - be it planned comparisons or post hoc tests - it is important you are fluent with both. Therefore, please navigate up and run the alternative set of pairwise comparisons to the one you originally chose - in short, if you haven’t had the chance to run planned comparisons, please do it now. If you haven’t yet run post-hoc tests, give them a whirl.

We didn’t end up running tests of homogeneity of variance for the ‘Likeability’ variable - remember, we decided not to analyze this data without either a transformation or a change to a non-parametric alternative. Regardless, just for practice, why not run a Levene’s Test - (see 3.1.4 Assumption of Homogeniety of Variance). How is it looking? Talk to your self or a study buddy.

- Before you finish, make sure you save a copy of the script that you have been working on by the end of the session. This provides you with the record - the digital trace - on what you have done. And it means you can come back and repeat any of the work you have performed.

Please end your session on the RStudio server, this logs you out of the server and stops any ongoing activities and tasks you have set up, maybe in the background.

- Please chill, you must be fatigued. See you next week and top work.