10.5 + 7 Week 2. Manipulating data

Written by Padraic Monaghan

2.1 Overview

This week, there are three mini lectures, and then a practical workbook to get you going with R-studio. Before the practical on Tuesday, please try to work through the practical workbook in your group.

Bring your questions (and/or answers) to the practical.

2.2 Learning Goals

By the end of Week 2, you should be able to:

Understand the importance of open data in psychology

Understand different types of data and how best to represent them

Understand bar graphs, scatter plots, and interpret patterns in these graphs

Open data sets in R-studio and manipulate those data

Use R-studio to make simple graphs

2.3 Lectures and slides

2.3.1 Lectures

Watch Lecture week2 part1.

Watch Lecture week2 part2

Watch Lecture week2 part3

Take the quiz on the lecture material (not assessed).

2.3.2 Slides

Download the lecture slides for:

2.4 Practical Materials

2.4.1 Workbook

In your group (or on your own until you’ve formed a group), work through this workbook, note any problems and questions you have, and come prepared to the online practical class to go through the tasks and ask your questions.

If you’ve done statistics using R-studio before then Parts 1 and 2 will be again largely revision for you. In this case, Part 3 is where you can focus your work.

Part 1 of this workbook reproduces what you saw in the week 2 part 3 lecture.

Part 2 gives you some more exercises in using R studio to revise last week’s material see this article for the psychology behind learning and memory effects of “spacing”.

Part 3 provides you with more practice at looking at others’ data and manipulating it.

Part 4 provides some more advanced methods for data manipulation.

Part 5 looks at different ways that data is stored, and how to adjust that.

Part 6 provides some extended extra practice in finding and investigating datasets.

If you have used R-studio before, then Part 6 will be where you will be developing some new advanced skills.

2.4.1.1 Part One: repeat the steps from lecture 2 part 3

Task Zero: making and opening an R script file

Open up the R server at https://psy-rstudio.lancaster.ac.uk

In R studio, at the File menu, select New File, then R script.

Now, we can put in our favourite sum to check it’s working.

At the top of the R script window type:

With the cursor on the same line as the sum click on the Run button.

In the console, you should see the sum being run, and the answer produced.

- Save the R script.

First of all, you can make a Directory/Folder to save the R scripts in to.

Your file structure can be anything you like, but here’s how I organised it: At the bottom right panel of the R-studio window, click on Folder. Add a new Folder, call it, say PSYC411.

Click on the PSYC411 Folder, and then make another new Folder, called, say “Week2”.

- Then, you can save this week’s workbook into the Week2 folder:

Click on the Save icon just above the R script window, browse to the Folder where you want to save the script (e.g., PSYC411/Week2), then name the R script file (e.g., workbook_week2.r) and Save.

The .r subscript indicates to R studio that this is an R script file.

Close the R script, by clicking on the little x next to the R script filename just above the R script window.

Now open it again. In the R studio window File menu, select Open File, and browse to where you saved your R script file and open it.

To make it easier to save and open files we can set what is called the “working directory” for R studio. Click “Session” in the menu at the top of the R studio screen, select “Working directory”, then select “Choose directory”.

Browse to the Folder where you are going to save your PSYC411 R studio files (for me this is Documents/PSYC411), and click Open.

Over on the right lower panel, you should now see all the files that are in this Folder - including psyc411_week2.r

Task One: open and check Practical week1 workbook script file

- Last week, we didn’t save a script (as we were just using the console for R studio). But here’s one I prepared earlier… Download the week 1 script file here. This also has the answers (but you can check last week’s answers via the main Week 1 page already too).

This has now downloaded the file on to your local computer. You now need to make it available in the psy-rstudio system. To do this, we have to “Upload” the file.

In the bottom right panel of R studio, click “Upload”.

For the Target directory, select the Folder in R-studio that you’d like to upload the file to (e.g., PSYC411/Week1 - maybe first of all you’ll need to make the Folder).

Then Browse to the file that is on your local computer, and click OK.

You should see it in the Files in the bottom right panel on R-studio.

- Now you can open psyc411_week1_workbook_answers.r in R-studio (either through File > Open File, at the top left panel, or just by double-clicking it in the Files in the bottom right panel). You can now look through this R script, check your commands and answers to the tasks from last week.

A really important feature to include in your r script are commments. Comments are preceded by a # which means that anything after the # on a line is not going to be interpreted as a command in R studio, but as a comment.

Good comment style involves consistent use of # to indicate different sections (e.g., you can use multiples of #’s to partition different sections of the results and make it easy to navigate, i.e., ########), and clear and succinct statements about why the command is there and what it is doing - see examples in the script file.

Comments help us to keep track of what each bit of our r script is doing, and, also importantly, enable others to figure out what on earth it is that we’ve done so they can reproduce our analyses, and access our data more effectively, in the spirit of open science.

Task Two: Opening a data file

Make sure you have open your script file psyc411_week2.r in R studio.

It’s generally a good idea to refresh and clear out R studio when you start a new session, so add this line to the beginning of your R studio file:

rm(list=ls()) - Next we are going to open a new data file.

Download the file PSYC411-shipley-scores-anonymous-17_18.csv

DO NOT OPEN THIS FILE ON YOUR COMPUTER – IF YOU DO, DELETE IT THEN DOWNLOAD IT AGAIN - THE REASON FOR THIS IS THAT IT CHANGES THE FILE FORMAT AND THEN WON’T OPEN PROPERLY IN R STUDIO.

Then, Upload the data file into R-Studio, and put it in PSYC411/Week2 Folder for instance.

Each row is one person’s data, and each column is a measure taken from the person. Columns are separated by commas, which is what the “csv” refers to” comma-separated values.

Next, we will set the “working directory”,this tells Rstudio where to look for the data. Click “Session” in the menu at the top of the screen select “Working directory” select “Choose directory”. Then, browse to the directory PSYC411/Week2 (or whatever you’ve called your folder), and click Open. If it worked, in the console it should say something like setwd(“M:/yourname/yourfiles/PSYC411/Week2”)

In R studio, we open csv files using a function called

read_csv()which comes from a set of functions that are stored in a library called “tidyverse”, we can install these functions by puttinglibrary(tidyverse)at the very top of our R script.

Type this command in the script file and then run it:

library(tidyverse)- Then type this command in the script file and run it:

dat <- read_csv("PSYC411-shipley-scores-anonymous-17_18.csv")Remember the dat <- notation, which means we put the data into an object called “dat”

- If all went well, we can then look at the data, using the function

View: In the script file type:

View(dat)and run it. It should open a spreadsheet where we can see the data.

- Have a good look around the data to see if you can make sense of it. For now, we will just focus on two variables from the data: subject_ID which is the participants’ anonymised number, and Gent_1_score, which is the participants’ score on the Gent vocabulary test, the first time they had a go (that’s what the 1 stands for). We can just pick out the columns of data that we want using the

selectfunction.

select is in the library called “tidyverse”, so we don’t need to load this in again because we already have.

summarydat <- select(dat, subject_ID, Gent_1_score)- Finally, let’s just have a quick look at these data. In the script file type:

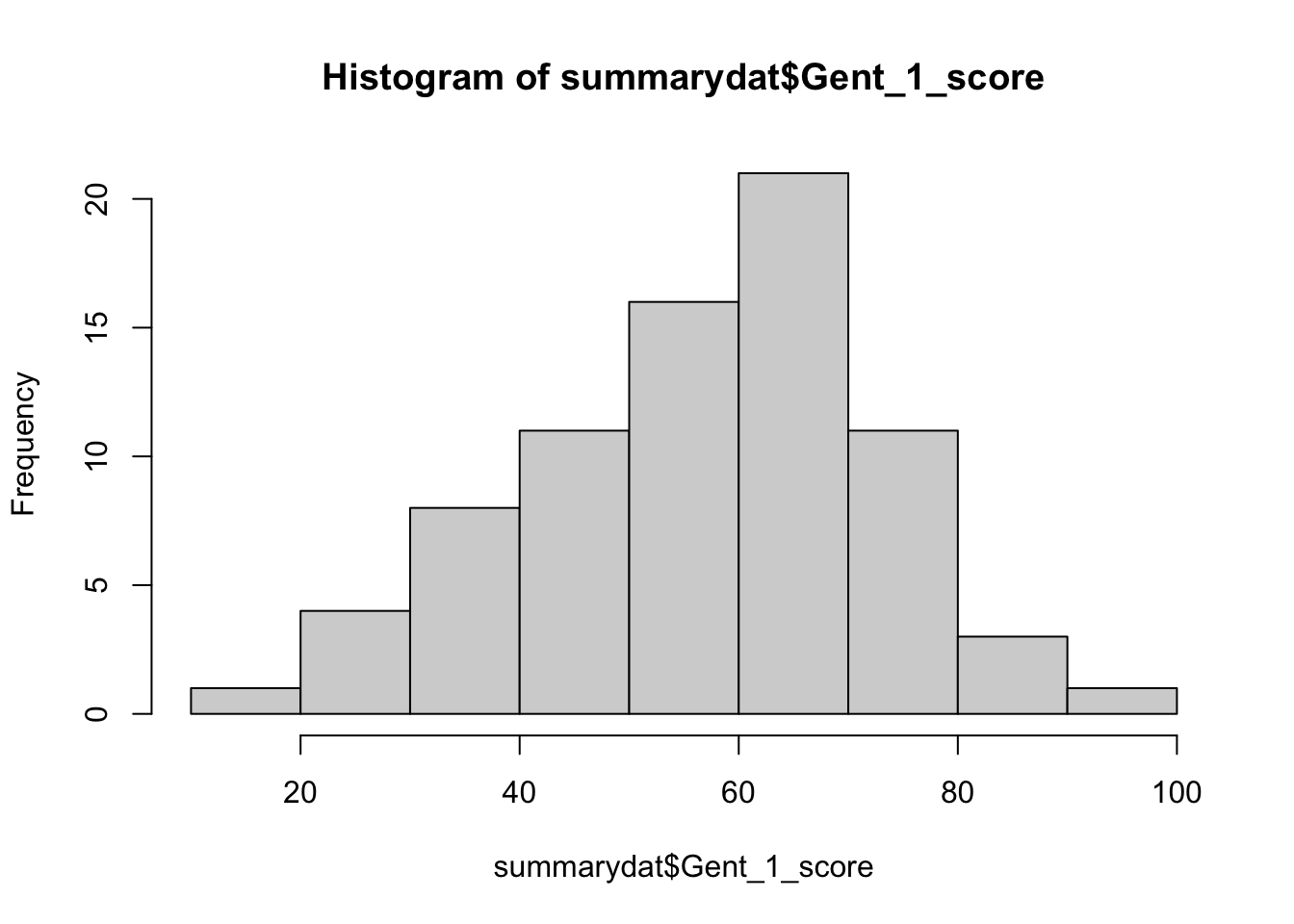

hist(summarydat$Gent_1_score)and run it.

- This will draw a histogram of the Gent vocabulary scores.

summarydat$Gent_1_scoremeans that we look at the Gent_1_score values from the summarydat data – the$indicates that this is one of the measures from the data. What kind of pattern does the histogram show?

2.4.1.2 Part Two: Revision from last week

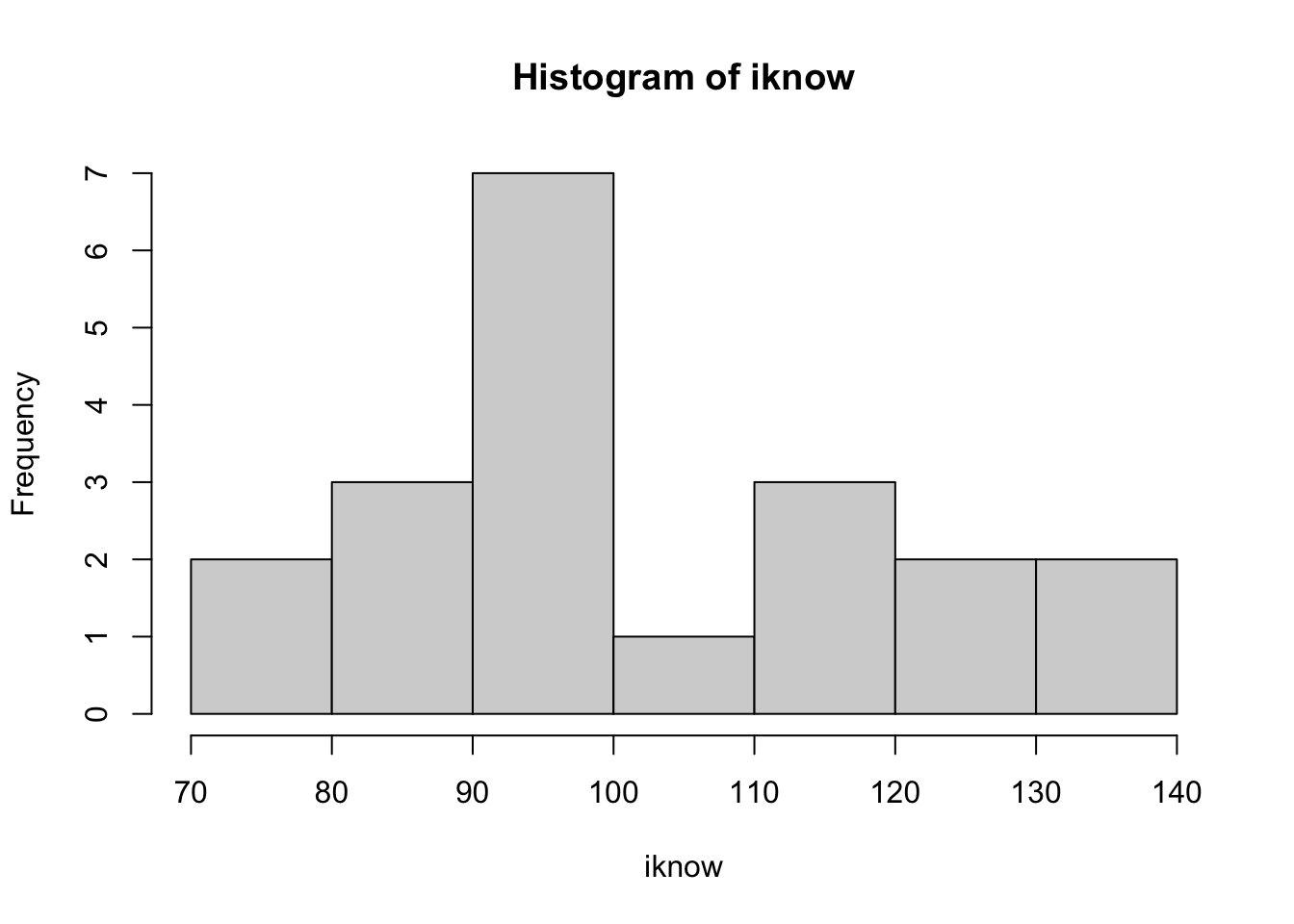

- Save your R script. Now, without looking at your notes, make a new object called “iknow”, and assign this list of numbers to it: 126, 76, 98, 124, 91, 88, 99, 115, 80, 113, 90, 92, 97, 134, 110, 92, 92, 87, 135, 115

- Remember to type these commands in the R script window. Next, get R-studio to give you the mean and standard deviation of this list of numbers, and draw a histogram of the iknow data.

2.4.1.3 Part Three: More practise at opening files and manipulating data

Task Three: Loading data into R-studio

- Download the data file called ahicesd.csv and Upload them into your directory in R studio: “PSYC411/week2”. Now do the same for participantinfo.csv.

These data come from this study: Woodworth, R.J., O’Brien-Malone, A., Diamond, M.R. and Schüz, B., 2018. Data from, Web-based Positive Psychology Interventions: A Reexamination of Effectiveness. Journal of Open Psychology Data, 6(1).

A brief description of the study is as follows: In our study we attempted a partial replication of the study of Seligman, Steen, Park, and Peterson (2005) which had suggested that the web-based delivery of positive psychology exercises could, as the consequence of containing specific, powerful therapeutic ingredients, effect greater increases in happiness and greater reductions in depression than could a placebo control. Participants (n=295) were randomly allocated to one of four intervention groups referred to, in accordance with the terminology in Seligman et al. (2005) as 1: Using Signature Strengths; 2: Three Good Things; 3: Gratitude Visit; 4: Early Memories (placebo control). At the commencement of the study, participants provided basic demongraphic information (age, sex, education, income) in addition to completing a pretest on the Authentic Happiness Inventory (AHI) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale. Participants were asked to complete intervention-related activities during the week following the pretest. Futher measurements were then made on the AHI and CESD immediately after the intervention period (‘posttest’) and then 1 month after the posttest (day 38), 3 months after the posttest (day 98), and 6 months after the posttest (day 189). Participants were not able to to complete a follow-up questionnaire prior to the time that it was due but might have completed at either at the time that it was due, or later. We recorded the date and time at which follow-up questionnaires were completed.

- Next, load the data into R-studio.

The first file is data from participants’ self-ratings of happiness and depression.

The second contains demographic information about the participants. Type this in your R script:

dat <- read_csv("ahicesd.csv")

pinfo <- read_csv("participantinfo.csv")run this command (type Ctrl-Enter), then type

pinfo <- read_csv("participantinfo.csv")and run that.

This has made two new objects – one called “dat” which contains the experimental data, and one called “pinfo” which contains the demographic information.

Task Four: Examining and manipulating data

- Let’s have a look at the data now.

View(dat)Run this command, and you should see the data appear above the console window. Have a good long hard look at it.

- The data contains:

id which is the participant number;

occasion which is whether this is the first (0), second (1), up to sixth (5) time they filled in the questionnaires;

intervention is which intervention they took part in with respect to attempting to promote their mood;

ahi01-ahi24 are the 24 items on the AHI happiness scale;

cesd01-cesd20 are the 20 items on the CESD depression scale.

Way over on the right are the total scores on the AHI and the CESD questionnaires.

- Now, view the pinfo data. How can you look at it?

Looking at the data replaced the source window, but the source is still there. Just above the View panel you should see a tab named psyc411_week2.r, click on that to get your source panel back. It will have a star/asterisk after the file name if it is unsaved. Remember it’s a good idea to regularly save your source file so you don’t lose work.

Now, we are going to join together the two files. Type this:

all_dat <- inner_join(x = dat, y = pinfo, by = c('id', 'intervention'))Question: what does the c(“id”, “intervention”) bit mean?

We’ve now made a new data set called “all_dat”. The “x = dat” bit is the name of the first datafile we want to join, the “y = pinfo” is the name of the second datafile we want to join, the “by = ‘id’, ‘intervention’” bit is the names of variables that the two datasets have in common.

- How would you join two data sets one called “data1” the other called “data2” together if they both have the variable “participantname” in common?

- Now we just want to keep a few of the variables – we’re not interested in the individual questionnaire items. So, let’s select the variables we want to keep:

summarydata <- select(all_dat, ahiTotal, cesdTotal, sex, age, educ, income, occasion, intervention)Where “all_dat” is the name of the object to take data from, and “ahiTotal, cesdTotal, sex, age, educ, income, occasion, intervention” are all the variables we want to keep.

- Have a look at the summarydata in the View. How do you do that?

Task Five: Investigate data

- The next task is to have a closer look at the distributions of the data. Let’s focus on the age of participants. To investigate one column of data from a dataset, you have to refer to it using the “$” symbol. So, to investigate the “age” column from the “summarydata” dataset, you would look at summarydata$age. Draw a histogram (bar graph) of the distribution of age in the participant sample.

- Now, let’s look at how the AHI and the CESD scores relate. To gain an impression of how two variables relate we can draw a scatter graph.

plot(summarydata$ahiTotal, summarydata$cesdTotal)What does the “$” do in this command? What relationship do you find between these two variables?

Now make sure you save psyc411_week2.r that contains all these commands that you ran. Close R studio, and Open R studio and make sure it’s saved all your work.

The list of commands is extremely useful for making science open and accessible to other researchers. It’s more and more common for psychology articles to make the R source files available so other researchers can reproduce the data manipulations and analyses used in the paper precisely.

4.2.1.4 Part Four: More (advanced) data manipulation

- For reading in more types of data, you can use commands other than

read_csv(). Have a look at https://support.rstudio.com/hc/en-us/articles/218611977-Importing-Data-with-RStudio and have a go at loading in excel files or text files with various formats into R studio, remember last week, we also loaded in spss .sav files using thespss.get()function in theHmisclibrary.

Another way to load in spss .sav files is to use the library called haven and the function read_sav which then works quite similarly to the read_csv file.

Note that using lots of different resources online is one of the points of using R-studio – everything is open and shared. It isn’t cheating - it’s what everyone who uses R-studio does, it’s what I did when I was checking some of the commands in this module - so do use google (or baidu, or any search engine) to explore other commands, and to get hints if you ever get stuck.

- What if the datafiles you wanted to combine together had different names for participants – maybe, for instance, in datafile “dataone” it’s called “id” and in “datatwo” it’s called “participant”. You can do this by specifying how variables in different datasets relate to each other.

Take a look at the help information for inner_join by typing ?inner_join then in the help pane on the right, scroll down to find the section titled “Arguments”, and read what it has to say about the argument “by”. See if you can understand how to join these files together. The examples at the bottom of the help section may be useful too.

- In the data set from Woodworth et al., we might want to just look at the pretests. We can use a function called

filterto pull out just some of the rows.

summarydata_occasion0 <- filter(summarydata, occasion == 0)This pulls out just the first occasion of testing (the pretest).

How would you pull out the second occasion of testing?

- How would you pull out just those participants who had the first intervention from the summarydata data?

- Back to the data set with just occasion == 0 selected. Now plot the relationship between the AHI and CESD scores at this pretest. What is the pattern now?

- How about just the participants who had intervention 1. What is the relationship between their scores on the AHI and CESD in the first test?

4.1.3.5 Part Five: Different ways in which data are stored: long and wide data format

When we look at other people’s data sets there are two generic ways in which they can be presented. The first is called “wide format”, and this is when several measures are presented on a single row in the data. This is the format of the data in the vocabulary scores: psyc411-shipley-scores-anonymous-17_18.csv, where there are three vocabulary tests each in different columns. The other format is called “long format”, and this is where each observation is on a different line – and if there is more than one observation from the same subject then that subject has multiple lines in the data. There are some functions in the tidyverse library that helps us convert from wide to long and long to wide. This part practises these conversions.

Task Six: Wide to long format conversion

Let’s go back to the psyc411-shipley-scores-anonymous-17_18.csv data. This should still be in the object called “dat”. If it’s not, then load the data again into dat, using the

read_csv()function.Make sure the

library(tidyverse)is loaded, if not, run the commandlibrary(tidyverse).The aim here is to convert the data so that each Gent vocabulary score is on a separate line, we use the

pivot_longerfunction for this. First we specify what the new object should be (datlong), then we say where the old data is (dat), then we make a new variable to keep the names of the tests (names_to = “test”), then we make a new variable to keep the scores from the tests (values_to = “vocab”), then we specify the list of old variables to combine into the new scores variable (c(“Gent_1_score”, “Gent_2_score”) ) – remember lists are written as c(). So, run this command:

datlong <- pivot_longer(dat, names_to = "test", values_to = "vocab", cols = c("Gent_1_score", "Gent_2_score")) - Have a look at the new object datlong that results:

View(datlong). This functionpivot_longerhas taken as input the data in dat, it has created a new variable called “test” which reports whether it is the Gent_1_score or the Gent_2_score that is the measurement, and a new variable called “vocab” where the actual scores are listed. Then, the following list of variables let’s the functionpivot_longerknow which variables from the object dat we are converting (or lengthening). It also includes all the other variables, but unconverted. How many rows of data are there now corresponding to data from subject_ID number 1?

- Let’s tidy things up so we only have subject_ID, and the Gent vocabulary scores by using select:

datlongsummary <- select(datlong, subject_ID, test, vocab)Task Seven: Long to wide format conversion

- Now, we will have a go at converting from long to wide format. Let’s start with the datlongsummary object. We will convert this so that Gent_1_score and Gent_2_score are listed alongside each other – one row per person. The command for this is the reverse of

pivot_longer, calledpivot_wider.Run this command:

datwide <- pivot_wider(datlongsummary, names_from = "test", values_from = "vocab")This command takes the data from datlongsummary and puts the different measures reported in the variable test into different columns again, filling in the values from the variable vocab.

4.1.3.6 Part Six: Extra practice finding and interpreting data sets

This part involves you exploring online psychology articles and finding an article which has made its data set available. More and more journals require data to be available when articles are published, an influential journal that has supported open science practices is Psychological Science. Go to the webpage of Psychological Science: https://journals.sagepub.com/home/pss. Browse the journal (you can view it on campus, off campus might be more difficult). Articles which have a dataset available have a “badge” indicating open data.

If data is made available, it is usually present as a “Supplemental Material” or via a link in the article (often data is stored on sites such as Open Science Framework (osf.io) or Figshare). For example, for this article:

at the end of the article there is a note on how to access the data:

Your task is to: download an article, download its data, and be able to describe what is in the data – i.e., what the rows and the columns in the data refer to. You can do this individually or as a group. At the next practical, you will talk one of the demonstrators through your description of the data.

You are free to explore the journal in its entirety to find an article that interests you, but some data sets can be really complicated to interpret. Some that you might begin with are as follows:

von Hippel, W., Ronay, R., Baker, E., Kjelsaas, K., & Murphy, S. C. (2016). Quick thinkers are smooth talkers: Mental speed facilitates charisma. Psychological Science, 27(1), 119-122. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0956797615616255

data is available on osf.io (open science foundation) have a look in the Archive of OSF Storage for this article, under “Clean Data”, “Study 1 data long format.csv”. See if you can figure that one out.

First, real life data, just like real life, is usually not complete – it contains missing values. The usual way to indicate missing values is “NA” in R. But if the data set contains missing values indicated in a different way, then you have to specify this when you input the data. So, if missing values are indicated by “999”, you have to do it like this:

read_csv("file.csv", na.strings="999")where file.csv is the file you are inputting. If missing values are indicated by “na”, you have to do this:

read_csv("file.csv", na.strings="na")if missing values are “.”, then like this:

read_csv("file.csv", na.strings=".")The second thing you might need to know is how to input files other than comma separated files. For excel files, you need to do this:

library(readxl), then you can use the commandread_excel("file.xls"), this should work for xls and xlsx files. For inputting data that is in text, but not separated by commas, have a look at the help for theread_csv()function:?read_csv. Hint – you’ll be looking to change the sep option for the read_csv command.

Sometimes, very annoyingly, a file is too large to upload into the r server.

This isn’t a problem if you have r studio installed on your own computer, but using the server it is rather annoying.

If the data is stored online somewhere, then if you can find the web address for the data file then you can upload it directly in the following way:

Here is an example on osf:

This is from the study Wald, K. A., Abraham, M., Pike, B., & Galinsky, A. D. (2024). Gender Differences in Climbing up the Ladder: Why Experience Closes the Ambition Gender Gap. Psychological Science, in press. and the data is here on osf

Navigate to the actual data file in osf, in this case we go to OSF storage, then Study 1, then data, then the file gender_study1_cleaned_data.csv.

Click on the file, then on the next screen click on the three dots that are next to the file name, then right-click on Download and copy the link. This is the web address for the data file gender_study1_cleaned_data.csv

Then, paste this into the read_csv command, and load it directly into an object in r studio, i.e.:

dat <- read_csv('https://osf.io/download/zstxk/?view_only=e7257f621e7c4b50b4032efd667d0db1')Importantly, you need to use single quotation marks ’, either side of the web address.

- See if you can find and load the data from any (or all) of these studies. Then have a go at exploring the data - e.g., can you first of all recreate the numbers in the paper (e.g., age and number of participants, mean and sd of the main dependent variable?)

2.4.2 Data

Here are links to all the data referred to in this practical:

2.4.3 Answers

The answers to the workbook appear below each question in the workbook, above, so you can check your answers.

It’s really important for your learning that you have a go first of all at the workbook before looking at the answers.

2.5 Extras

- Optionally, watch Brian Nosek’s keynote at the 2018 British Psychological Society conference on the replicability crisis (note hosted on youtube).